Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Good morning. Yesterday was a good day. The Nasdaq had its best session since May and bitcoin prices gained more than 2 per cent. Various theories have been floated about the good vibes — dip buyers making a comeback; revived rate cut hopes; “a very good telephone call” between Trump and Xi (Trump’s words). Or just a case of holiday cheer ahead of Thanksgiving? Let us know your thoughts: unhedged@ft.com

More on valuations

Last week, when Unhedged gave its bear case for the year ahead, we carefully excluded high valuations. High stock prices tell you almost nothing about what markets will do in the short term. We used this scatter chart, which maps year-end S&P 500 valuations on to year-ahead price returns, to illustrate the point:

Several readers wrote to say valuations are a good guide to longer-term returns. They’re right. Here’s the same chart, but with 10-year returns annualised on the vertical axis. The R-squared relationship (the degree to which variation in returns can be explained by initial valuation) goes from 0.03 to a meaty 0.69.

Notice, however, the big blob of dots in the middle of the chart, where annual returns cluster around 5 per cent and 12 per cent and P/Es cluster between 15 and 20. Here, the relationship is weak. It’s only when valuations get to extremes that they tell you very much about long-term returns. Fussing about the difference between a 15 and 20 P/E market probably won’t make you much money.

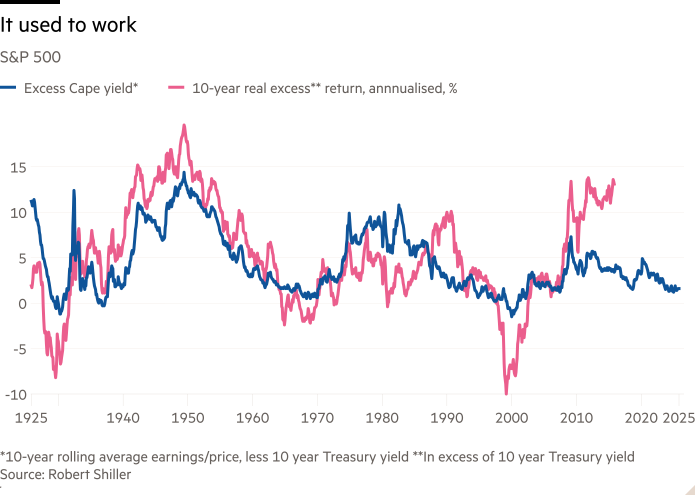

This is a small sample and a simplification. Robert Shiller of Yale has laid out a much more refined version of the relationship, one which accounts both for the cyclicality of earnings and the effect of interest rates. The S&P 500 “excess Cape yield” takes an earnings/price ratio — that is, an earnings yield — using 10-year average earnings as the numerator, and then subtracts the 10-year Treasury yield from the result. So the “excess” means “in excess of the bond market”. It has been a pretty good indicator of 10-year forward equity performance over the past century, as this chart shows:

However, the most interesting part of that chart is the period since 2011 or so, when 10-year returns (the pink line) have started to break above their traditional relationship with the excess cape yield (the blue line). That breakout explains the agonies valuation-oriented investors have suffered for the past decade or more. S&P 500 valuations have waved a caution flag on and off for years, and anyone who heeded it has missed out on great returns. (As a person who got their start in value investing, I was a member of this unhappily underinvested club for several years).

Right now, the excess cape yield is almost as low as it has ever been. Should we look back at the past decade and ignore the alarming implications? Some people think so (see the One good read, below).

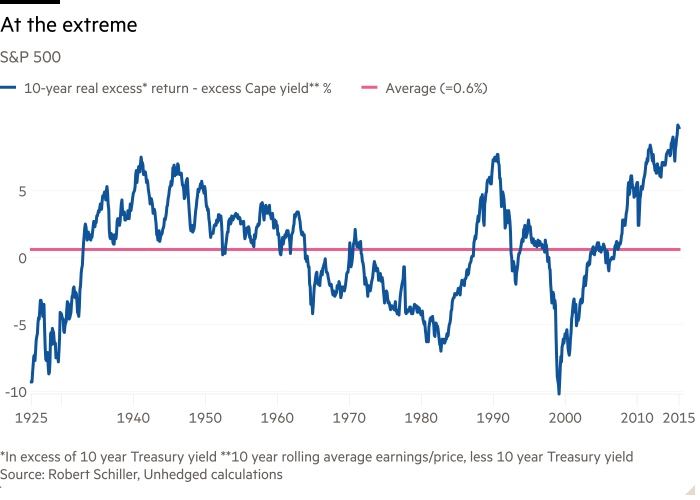

Let’s cut the data a slightly different way. The chart below shows 10-year S&P 500 excess returns minus the initial excess cape yield. That is, it shows you how much more or less the markets delivered than the cape yield “promised” (the red line is the average):

What does this chart say? At the risk of playing fast and loose statistically, it says average 10-year excess returns are just a shade (0.6 per cent) higher than the starting excess cape yield. And while excess returns usually don’t stray more than, say, six percentage points in either direction from that average, they do swing around quite a lot. The last 10 years have delivered much higher excess returns than the excess cape yield would have predicted but — and this is the crucial point — the divergence is not unprecedented. In March of 1999, for example, the excess cape yield was a horrifyingly low 0.21 per cent and annualised real returns over bonds over the next 10 years were worse — minus 10 per cent. But that divergence didn’t last, and our guess is that the current divergence, in the other direction, won’t last, either.

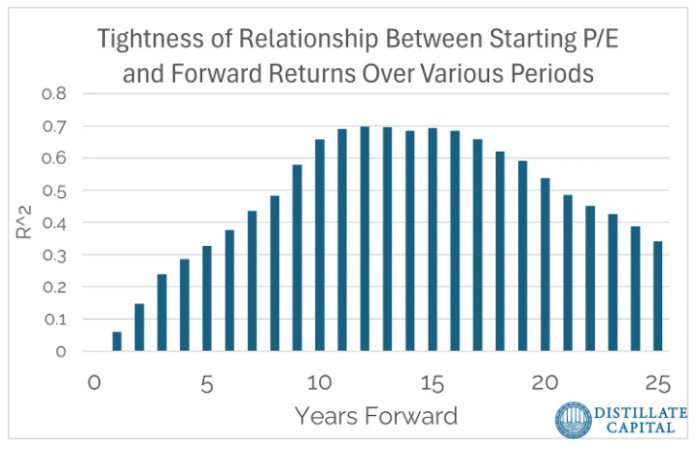

Value investors have been making points like this for a long time. But there is a related point that I hadn’t thought of until it was pointed out to me by Jay Beidler of Distillate Capital. Over the long term, valuations do tell you something about returns, but over the very long term, they tell you less and less. This is because the effects of swings in valuation cancel each other out over very long periods, and the steadier sources of return — earnings growth and dividends — come to predominate. Here, from a recent Distillate note, shows the R-squared for starting valuations and forward returns for different periods:

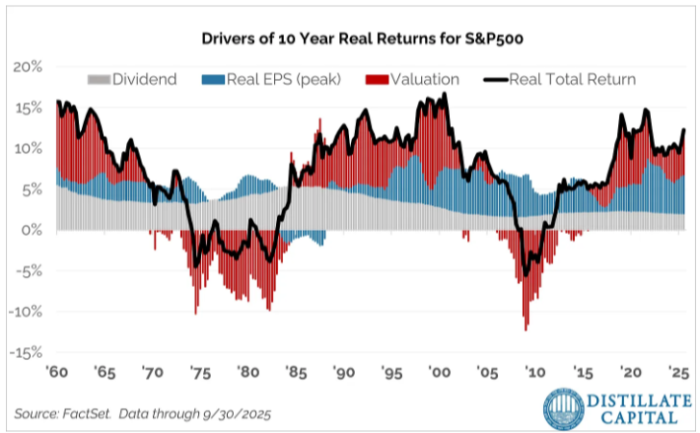

As another way to visualise this slightly slippery point, here is a chart from Distillate showing the sources of 10-year returns on the S&P 500, divided into real earnings, dividends and changes in valuation. Valuations mean revert; earnings and dividends compound:

There is an important lesson in that chart for investors under 40 or so: don’t worry too much about valuations. Just get started, and buy some diversified equity indices if you can. Valuations will take care of themselves over the next 30 years. And if they don’t, you’ll probably have bigger problems than your investment portfolio.

One good read

Optimism unbound.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.