Good morning. Did someone say credit cockroach? The Wall Street Journal reports that BlackRock and a group of other lenders have lost $500mn to a “breathtaking” accounts receivable fraud. This just a few days after BNP Paribas reported a €190mn “credit event,” also involving fraud. Email us with the name of a good exterminator: unhedged@ft.com

And don’t forget: the New York edition of Alphaville’s Pub Quiz is on November 11! Unhedged will be there, along with every other self-respecting finance nerd in our great city! It will be fun! Details here.

Tech earnings

Three months ago, during the last Big Tech earnings season, Unhedged tried to explain the differences in performance among the big techs (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, Tesla). We concluded that the picture was pretty simple: the market likes revenue growth. “Grow sales . . . stock goes up. Occasionally the market is a pretty simple beast,” I wrote. This is the view that, for all their unimaginable size, the big techs still trade like start-ups. Investors want to see world domination (for which sales growth is a proxy) and are happy to worry about profits later.

I now think that’s wrong. Yes, sales growth monster Nvidia has performed the best, and near-growthless Tesla has performed the worst in recent years. But take out those two extremes, and the picture is muddier. A vivid recent example of this is the different market responses to the third-quarter earnings of Alphabet and Meta.

Alphabet announced a big increase in both revenue and earnings per share, and management warned that investment in artificial intelligence would lead to significantly higher operating and capital expenses next quarter and next year. Its shares rose 3 per cent on the news. Meta announced broadly the same thing, and its shares fell 11 per cent on the news. News reports focused on Google’s growth and on Meta’s expenses, but the numbers were not all that different. In fact, Meta’s sales grew more than Alphabet’s, in absolute terms and relative to expectations. Despite this, after the leap in Alphabet’s shares, they now trade at a 20 per cent premium to Meta’s on a price/earnings basis (and Meta, at 20 times forward earnings, is easily the cheapest of Big Tech stocks).

There were some important differences in the earnings per share results, if you look a bit more closely: Alphabet’s growth accelerated and crushed expectations, while Meta’s, although strong, decelerated and merely edged past expectations.

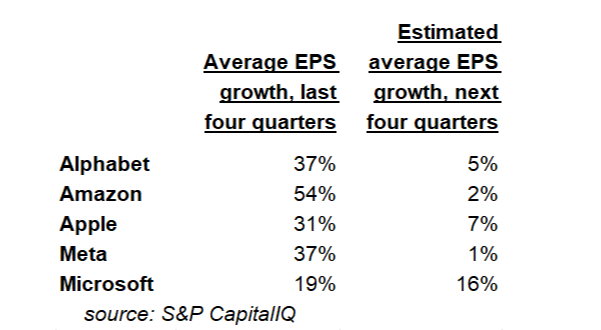

Widening the lens a bit makes the point clearer. Here is revenue growth over the past four quarters, and analysts’ expectations for revenue growth over the next four quarters, at five of the big techs:

Meta’s revenue is growing faster than Alphabet’s and is expected to keep doing so. And generally, all of the companies are expected to hold sales growth steady-ish in the year to come. Earnings are a very different story:

All five of the companies’ earnings are expected to slow significantly next year — partly because the past year has been exceptionally good cyclically, and partly (for all of the companies but Apple) because of heavy AI spending. At Meta and Amazon, profits are supposed to grind down to nearly nothing (though, after Amazon’s banner third quarter reported last night, estimates for next year seem likely to rise; Alphabet’s estimate may get a boost soon too). Meta is in a class of its own, however, when looking at estimates, for this year and next, for capital expenditures and free cash flow:

Meta is expected to increase its investments much more than its peers, in both dollar and percentage terms, and it is correspondingly the only one of the five that is expected to see free cash flow decline next year. The market is not giving carte blanche to the “AI hyperscalers” to spend what they want on data centres. Meta is the only company that is increasing spending faster than it is increasing free cash flow, and the market is punishing it accordingly.

This may seem crushingly obvious: of course markets care about earnings and free cash flow. But the AI boom narrative has been that it is a no-holds barred race for computing power and AI market share, profit be damned. This is absolutely not the case: Meta shares’ divergent performance shows that the market is setting guard rails for the big techs, and most of the big techs are respecting them.

(Armstrong)

Trump’s China deal

After all the excitement running up to the US-China talks at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Korea, the US and China came to a deal that markets did not care about at all. The economic and financial impact of the agreement was so modest in scale that it was completely overshadowed, in the stock market, by tech company earnings.

A few horses were traded. Trump announced that China would purchase “massive amounts” of soyabeans (12mn tonnes this year, and at least 25mn tonnes annually for the next three years, according to Treasury secretary Scott Bessent). China postponed the rare earths controls it announced earlier this month. Both countries suspended measures targeting each others’ shipbuilding industries. The US is holding off on its extension of tech-related export controls and halving of the fentanyl tariff rate on China, to 10 per cent.

The tariff cut is a bit of relief for China. But the benefit will be marginal. Louise Loo of Oxford Economics forecasts it adding just 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points to China’s growth next year. The soyabean purchases are just a return to the levels of last year.

In sum, the agreement is less a deal than a moment of détente. Loo points out that “the four ‘Ts’ — Taiwan, transshipments, TikTok and chip technology” — went mostly untouched. “All the large economic and non-economic issues that Trump, and prior American presidents have complained about weren’t even on the table”, Bill Reinsch of CSIS said.

According to Alan Wolff of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, “We don’t have a great deal. We have a pause.” Eswar Prasad of Cornell University agrees:

It’s not a deal, it’s a framework, or even an outline of a framework, so the uncertainty hasn’t been resolved in any substantive fashion . . . If one were to think about any major gains the US has made relative to where we were a few weeks ago, there are gains. But if you go back to January, before Trump took office . . . its hard to see how much the US has gained

There was another — more interesting and less direct — development in US-China trade relations this week that came in the form of US trade agreements with Cambodia, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand. These agreements specifically call for the enforcement of measures to combat transshipments made to evade US duties, which was not addressed directly in the China “deal”. There are also clauses in the agreements with Malaysia and Cambodia that threaten the reimposition of “liberation day”-level tariffs if the two countries enter new bilateral free trade agreements or “preferential economic agreement[s] with a country that jeopardises essential US interests”.

A little of the pressure has been removed from US-China trade relationship, but it remains deeply adversarial.

(Kim)

One good read

This newsletter was amended after first publication to correct the figure in the first paragraph to $500mn

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.