On Friday, in a classic case of an arsonist calling the fire department, Donald Trump announced tariff exemptions on foods that the US struggles to grow in volume, such as oranges, tomatoes, bananas and coffee. Unhedged expects further outbreaks of rationality before long. Are we too optimistic? Email us: unhedged@ft.com.

Is there nowhere to hide?

Aswath Damodaran is unusual among market experts in that he is analytical and sceptical, and at the same time a true enthusiast. He likes investing, believes in markets, and has a strong risk appetite (all of this is on display in Unhedged’s conversation with him last year). This is why his recent interview on the Prof G Markets Pod struck me as important.

Damodaran thinks that a “market and economic crisis that is potentially catastrophic [is] not being priced in by markets right now, and the chance of it happening is perhaps greater than it’s been at any time in the last 20 years.” His worries are focused on the big tech stocks and, he says, “If the Mag Seven go down by 40 per cent, it’s not like the industrials are going to hold their value, the kind of panic that’s going to ripple through [markets].” Damodaran is trimming his exposure to stocks and holding more T-bills, and for the first time is considering the wisdom of parking some wealth in non-financial assets like gold or collectibles.

His concerns seem to have two roots. He thinks the AI story is wildly overbought. The revenues implied by AI company valuations are unrealistic. The valuation of Nvidia, in particular, is mad: it implies trillion-dollar revenues and 8 per cent gross margins out to the far horizon. At the same time, nothing in the market is cheap, because “we live in a world where everything seems to be correlated . . . correlation has risen to the point where the classic rule of [diversification across sectors and geographies] doesn’t apply . . . it makes investing a lot more dangerous.”

I have been less pessimistic about the AI bubble than Damodaran recently, for reasons that will be familiar to regular readers: sane valuations and strong free cash flow for several of the Mag 7; a growing US economy that may grow faster still next year; a world awash in savings that have to go somewhere. I should also note that while half of my own savings are US stock indices, I also own cheaper global indices, some bond funds, and maintain a meaty cash position. This cautious approach, which has had big opportunity costs for the past few years, helps me remain philosophical about bubbles. If we have a crisis, I will have some capital I can put to work in suddenly cheaper equities.

Some context. Damodaran’s core market valuation tool is a prospective equity risk premium. To simplify, the ERP takes current prices and estimates for future earnings, solves for the rate of return that matches the two, and then subtracts the risk-free rate from it. As of the first of November, his estimate of the ERP was 3.7 per cent. While he calls anything below four his “red zone”, the ERP is far from its 2000 lows or the lows of the 1960s:

Still, the dangers of buying into a sub-4 ERP are worth contemplating. A good example, particularly in the current context: suppose you put money to work in the S&P 500 on January 1 1970, when the ERP was about where it is now. Over the next decade, the market worked its way sideways, ending with a return, with dividends reinvested, of 77 per cent. Sounds OK? It wasn’t. Prices, as measured by CPI, rose 120 per cent over that decade. In real terms, you lost almost half your money.

As for Damodaran’s “no place to hide” view, it’s informative to look at this year’s “liberation day” shock. This was a policy shock, not a bursting bubble shock, but it still holds lessons. The S&P 500 fell 20 per cent between February 19 and the April 8 bottom, and mid-cap stocks, despite their cheaper valuations, did just as badly. The S&P equal weight, which again is cheaper because it gives less weight to the big expensive techs, did only a bit better. But cheaper global stocks did provide a bit more of a buffer. UK stocks were down just 9 per cent and European and Japanese indices by 12 per cent.

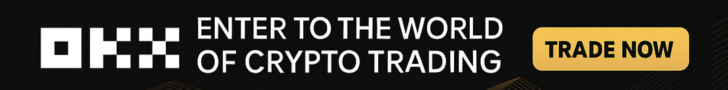

Going back to the great financial crisis, though, international diversification or holding the equal weight index was no help at all, if you held on all the way to the market bottom. There was some differentiation early on, but the final crushing sell-off in late 2008 wiped it out:

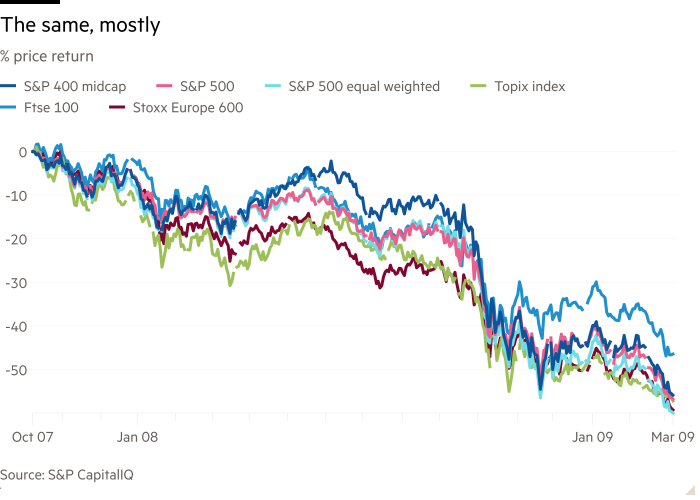

Going further back, the dotcom crash, which one might argue has more in common with a hypothetical AI meltdown, was a different story. Avoiding the expensive big caps helped. Peak to trough, the S&P 500 equal weight and the S&P mid-cap outperformed by 16 and 18 points, respectively.

We should keep this “outperformance” in perspective: a 30-point drawdown is horrible, even if less horrible than a 45-point one. Cash was the place to be. What did provide protection in 2000, however, was sector selection. Look at the outperformance of consumer staples and the misery in tech:

Still, I can only manage a mild level of disagreement with Damodaran’s “nowhere to hide in stocks” comment. He points out, as others have, that the AI boom is not just a financial phenomenon. A big chunk of the growth of the real economy is being driven by data centre construction. All sorts of companies are benefiting from this infrastructure boom. One example: in the third quarter, all the growth in operating profit at the heavy machinery company Caterpillar came from its energy and transportation segment. Here’s the CEOs commentary on that business:

In Energy & Transportation, we expect strong growth in full year sales for power generation compared to last year. Demand remains robust, driven by data centre growth related to cloud computing and generative AI.

Not all the growth in the economy comes from the AI building boom, as some contend, but a major slowdown would cause pain beyond just the tech industry. If there is one, diversification away from the cap-weighted S&P into equal- or fundamental-based indices, or into international stocks, will help, but probably only a little. Staples stocks, a much-hated category recently, will probably outperform meaningfully. But what will really help is reasonable cash and bond allocations, and a cool head.

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.